As an entry point to understanding heart rate training zones, V02 max, and lactate, we’ve built 3 and 5 zone training models. In case you need to review: Heart-Knock Life: Understanding Heart Rate Training Zones, V02 Max, & Lactate Threshold.

The question we left off on was, “How do we use heart rate zones to get better?”

In order to answer this question, let’s clarify what better means from a physiological perspective. Generally speaking, the goal of endurance training is two fold:

1) To maximize energy production

2) To minimize fatigue

More energy and less fatigue allows runners to run faster, wrestlers to grapple harder, and athletes of all types and stripes to work harder for longer. In endurance sport, this is a direct path to victory and for most athletes, this is an important component to better performance.

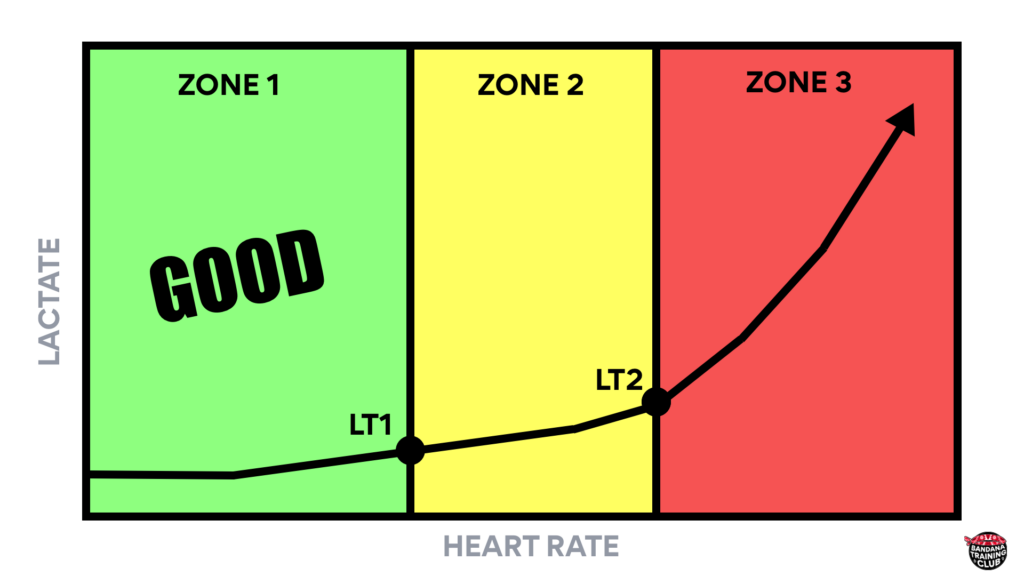

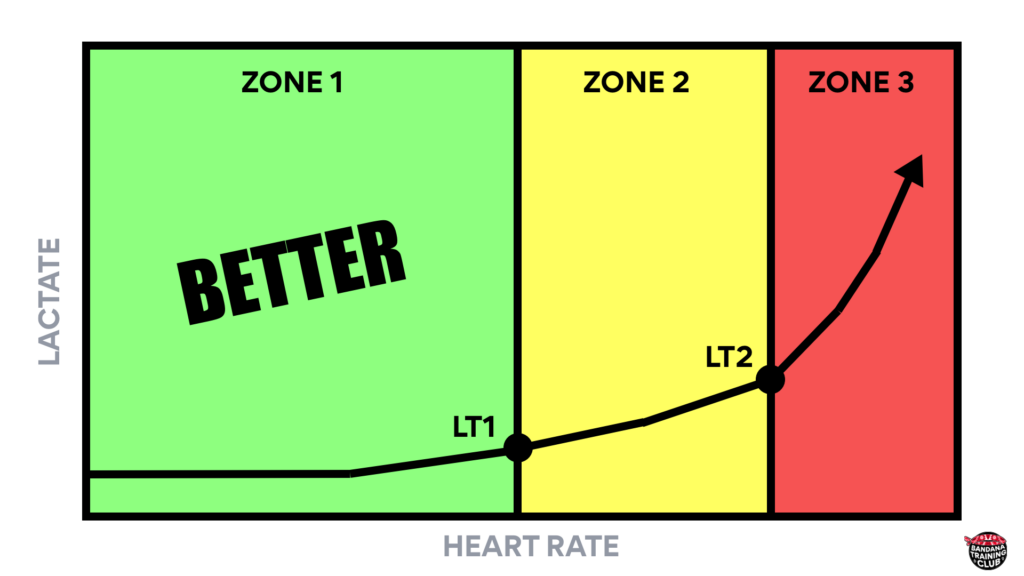

If we put this in the content of heart rate and lactate, better conditioning athletes are going to move their lactate curve to the right, producing less lactate at any given intensity.

So if this was our original 3 zone lactate graph, a better conditioned athlete would look like this…

As you can see, the goal is to expand our aerobic base and push our anaerobic threshold closer to our V02 max.

Now the question becomes, how do we do this?

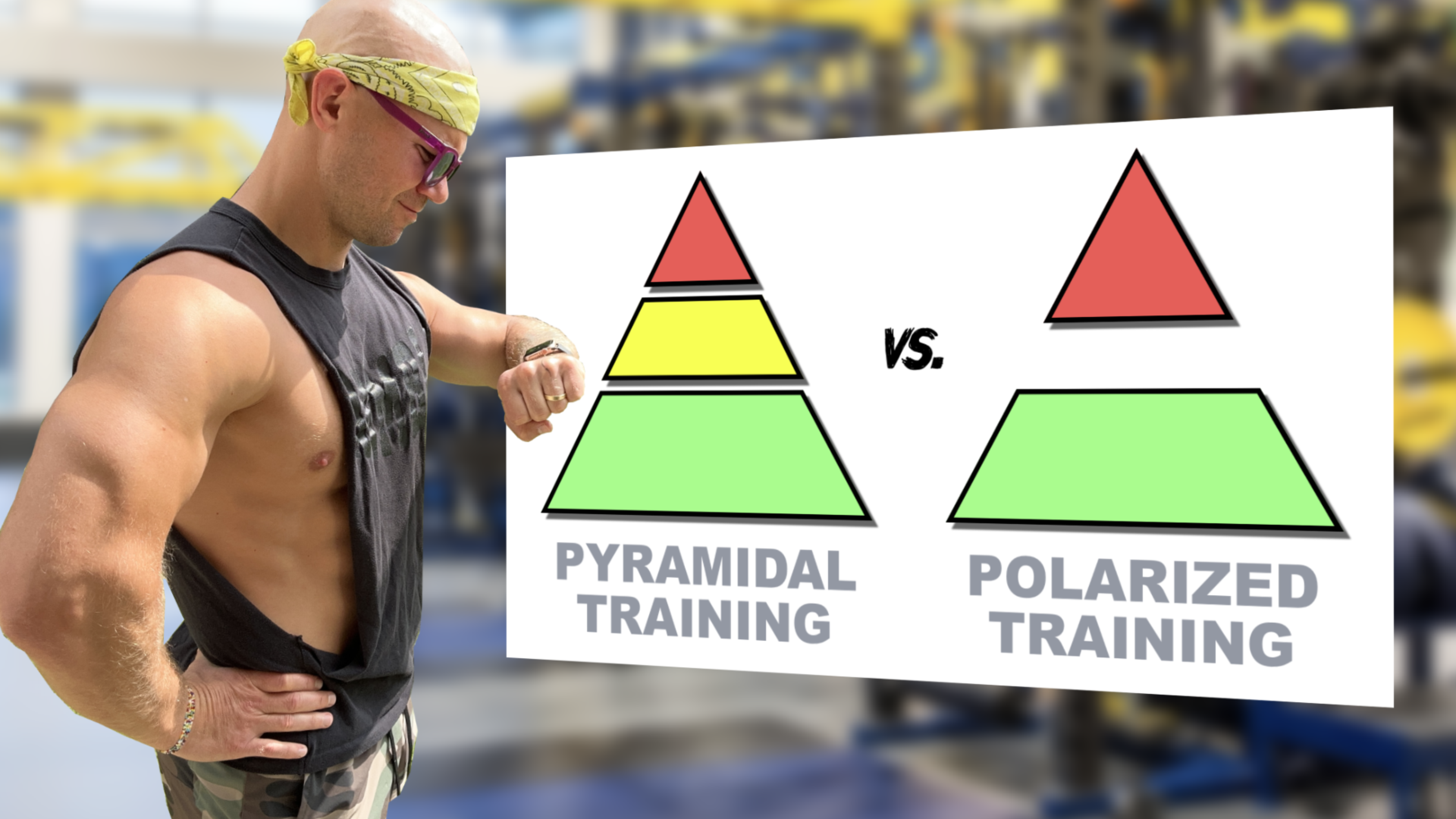

If you ever want to do something well, it’s a good idea to study how the best in the world do it. Success leaves clues. For insight, we turn to the world of endurance sport where two primary philosophies have been shown to improve performance to a greater extent than other models (Casado et al. 2022). One is called Pyramidal Training and the other Polarized Training.

In simple terms:

Pyramidal Training – 70/20/10 – spending roughly 70% of your training at low intensities, 20% of your training at moderate intensities, and 10% of your training at high intensity.

Polarized Training – 80/20 – spending most of your training at low intensities, a bit of your training at high intensity, and very little training in the middle.

A little about the backstory here…

Pyramidal training has been the mainstay of endurance prep for generations. It’s relatively simple and follows a logical linear progression. Most time in easy zones, some time spent training a bit harder, and a little time spent at or near max.

About 20 years ago, Dr. Stephen Seiler, an American-born exercise physiologist in Norway, noticed that many elite endurance athletes were spending a lot of their training at low intensity and the rest of their training at high intensity. They spent very little training in the middle. Matt Fitzgerald wrote a bestselling book based on this insight called 80/20 Running: Run Stronger and Race Faster by Training Slower.

The thought process popularized by 80/20 Running is that you can either push these thresholds from the bottom or pull them from the top, but spending time in the middle isn’t doing much good. These miles even become known as junk miles – hard enough to require additional recovery without additional benefits.

What does the science say?

A recent systemic review from Casado and colleagues in 2022 showed that runners in their preparatory and pre-comp phase seemed to benefit from a pyramidal approach while runners during the competitive season benefited more from polarized training. They also showed that as race distance increases, runners tend to utilize a more pyramidal approach. For example, marathon runners tend to use more pyramidal training while 1500-m runners tend to rely more on polarized models. This makes sense because 1500-m runners are going to accumulate more volume at higher intensities. Included in this review was research from Filipas and colleagues that compared 16 weeks of pyramidal and polarized training, illustrating for the first time that a shift from pyramidal to polarized was more effective than pure pyramidal or polarized training alone (Filipas et al., 2022).

Here’s what’s clear:

For endurance athletes, a large amount of training should be at low intensity (Zone 1 in a 3 zone model / Zone 2 in a 5 or 6 zone model). How you choose to divide the rest of your training comes down to what race you’re prepping for, how much time you have to train, how well you recover, your training age and history, how much strength training you’re including in your routine, and your personal preferences.

Speaking of things that work exceptionally well, I use both in my programming.

I tend to start with a more pyramidal approach because I keep the high intensity work to a minimum. I gradually work my athletes into higher and higher intensities, at which point their program is more polarized. At some point in their training cycle, we replace some of the shorter duration anaerobic intervals with longer duration aerobic intervals, at which point their training is once again more pyramidal. We also lift more than every run program I’ve ever reviewed which helps keep my athletes strong, lean, and injury-free.

All said, the moral of this story is that most of your training should be done at low intensities. How you chose to divvy up the rest of your training should be determined by you, your coach, and hopefully a little bit of science.

If you’re learning from these posts, please follow me on social media (links below) and consider signing up for the Bandana Training Club which contains an entire catalogue of training programs and sport science related content.

Works Cited

Casado, A., González-Mohíno, F., González-Ravé, J. M., & Foster, C. (2022). Training Periodization, Methods, Intensity Distribution, and Volume in Highly Trained and Elite Distance Runners: A Systematic Review. International Journal of Sports Physiology and Performance, 17(6), 820–833. https://doi.org/10.1123/ijspp.2021-0435

Filipas, L., Bonato, M., Gallo, G., & Codella, R. (2022). Effects of 16 weeks of pyramidal and polarized training intensity distributions in well-trained endurance runners. Scandinavian Journal of Medicine & Science in Sports, 32(3), 498–511. https://doi.org/10.1111/sms.14101

Jones, A. M., Kirby, B. S., Clark, I. E., Rice, H. M., Fulkerson, E., Wylie, L. J., Wilkerson, D. P., Vanhatalo, A., & Wilkins, B. W. (2021). Physiological Demands of Running at 2-hour Marathon Race Pace. Journal of Applied Physiology (Bethesda, Md. : 1985), 130(2), 369–379. https://doi.org/10.1152/japplphysiol.00647.2020